My Father

... and food insecurity

My father was sent to the Home for Malnourished Children as a child. It was the 1930’s, during the Great Depression. His parents were immigrants – no English, and unable to feed their family.

Hunger is an all too common reality for immigrants all over the world. Hunger changes a person. It changed me, just through the stories of my father.

To this day, I am moved to tears when i read about hungry children.

My sister and I grew up with his stories of food insecurity. It never left him his whole life. At the Home for Malnourished Children he learned not just to eat, but to over-eat. He taught us the same. Our family, as a treat, often went to all-you-can-eat restaurants. There, Dad would happily instruct us – go back to the buffet at least 3 times. Fill up those plates.

i did so with pleasure. Eating is great. Earning my fathers approval – even better. I remember well his approving gaze at my 3rd return from the buffet with a minor mountain of food on my plate.

The predictable result? I can always eat more. My Spanish speaking friends called me el aspirador, the vacuum cleaner. Before I was 66 years old, I literally did not understood that there was such a thing as feeling of “full” was. He trained that out of us. I simply did not understand why others stopped eating when delicious things were in front of them. I cleaned my plate and often, the leftover food on plates of others around me. The only fullness i had learned was the feeling of physical pain from being overstuffed

Other than that, always room for more. And even then, why not. just one more mouthful …

The poverty of his family meant that my father was able to go to college only because he had served in the army as a private in World War 2 and afterward, the GI Bill paid for his college.

No surprise then that he passionately believed in free education for all.

Including, free for me, his son.

He was willing, eager even, to pay my way through college. For him, it went without saying that one goes to college to prepare for a career, to study something that allows you to have a stable, prosperous, successful life. It wasn’t about getting rich, that was not the emphasis, but it was about financial security. One never knows if another Great Depression is about to come crashing down on us again.. So creative areas to study, literature, art history, were fine as additional electives, but if it wasn’t something leading directly to a substantial solid career, he’d call it “basketweaving”, his catchall term of derision for all such subject areas.

But although i knew this unspoken assumption was always in his mind, it was not in mine. He paid for the piano lessons i wanted, because he believed in being a good parent, but we both knew that was an “additional” interest.

College itself was another matter.

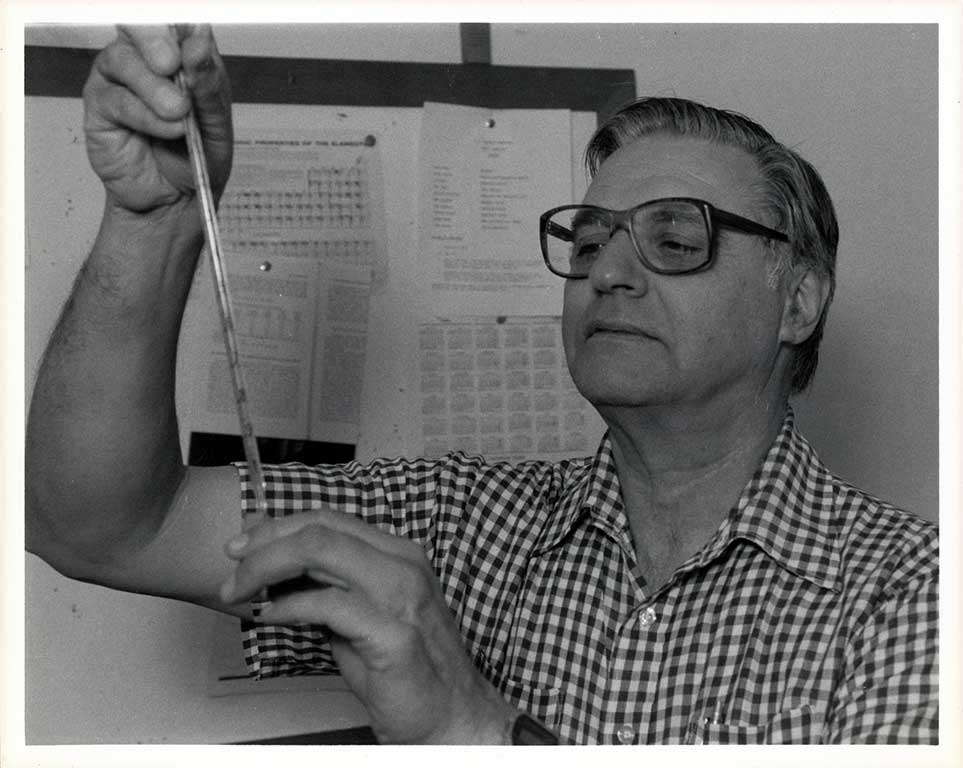

When I told him I wanted to study film making in college, the answer was, “No.”

He never wanted me to study film making.

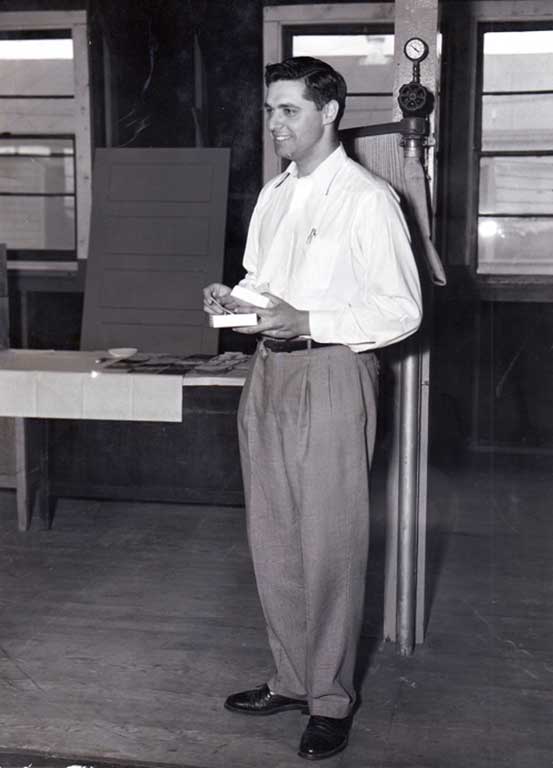

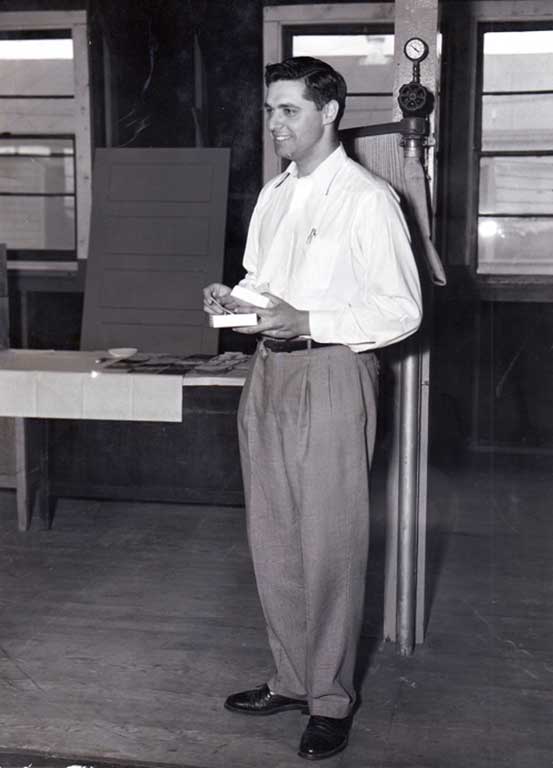

He told me he wanted me to go to college so i could get a real job, something with a retirement plan at the end and genuine security along the way. Like he did. He worked for the government, a scientist in the Department of Agriculture. He loved the science part, but was bored by his actual work and the assignments he got, but as he often said, “at least the government will never go out of business.”

That security satisfied his inner malnourished child.

My interest in any of that creative stuff?

That was fine for the children of the rich.

If I wanted him to pay for college, i had to study something useful.

My memory of that conversation was that it was surprisingly easy.

He thought i was asking permission and he said “no”. I had no intention of asking his permission. I was just telling him what my plan was. When he said no, i just said, “okay”

His attitude seemed inflexible but fair to me. It was his money after all. He said “no.” I said “okay” and then surprised him no end. I told him i would drop out of school, start to work, earn my own money, apply for financial aid, and study what i wanted, not what he did. All i asked is that he stop claiming me as a dependant on his income taxes, since i wouldn’t be one anymore.

In retrospect, i see that on that day, i became a man.

He was stunned and surprised. He never imagined this outcome. But he was fair about it, and supportive of my decision. He stopped claiming me as a deduction on his income tax and a year later with entry level jobs and financial aid, i returned to college. Dad gently looked the other way as my Mom would lovingly slip me a $20 bill each time i’d visit home.

In time, just as i learned food insecurity from my Dad; i learned the steady modest generousity from my mom. Many nieces and nephews and god-children and children of good friends know this well, as i slip them some cash and explain they need not thank me, but thank my Mom; and tell them one more time about how she showed love in this way.

After I graduated and started working in the film industry, Dad worried, of course. He never understood working freelance in the film business. Working film to film with unemployment in between seemed to him to be a nightmarish way to live, but he never forced me to carry his worries. He just repeatedly wondered when i was going to get a real job, and stop this fooling around.

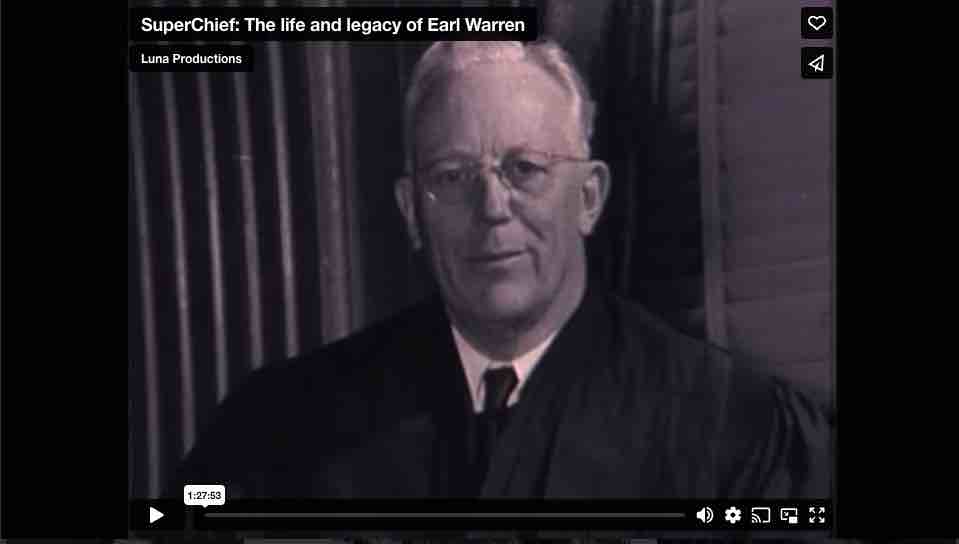

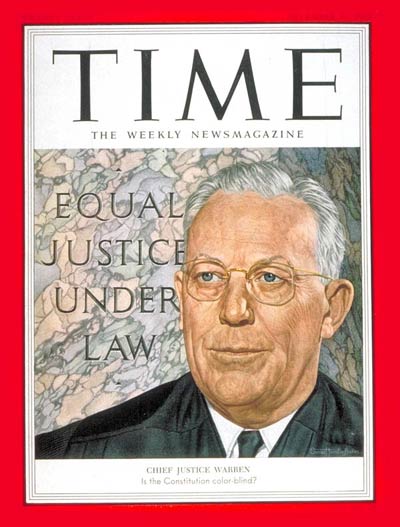

Eventually he did change his mind, at least for a moment. I had edited a documentary that was nominated for an Academey Award and he and i went to the screening of the 5 nominated films, an all day affair of looking at films that was exhilerating and exhausting.

The film i had edited was “SuperChief: The Life and Legacy of Earl Warren.” Earl Warren was a hero of my father. Warren was a heroic Supreme Court Justice who ended legal segregation in US public schools and a number of other huge steps forward in social justice. My father was moved by the film, and moved by the whole day such that at the end he took my hand, In a very formal way he shook it and said, “Well, i guess you do have a career after all.”

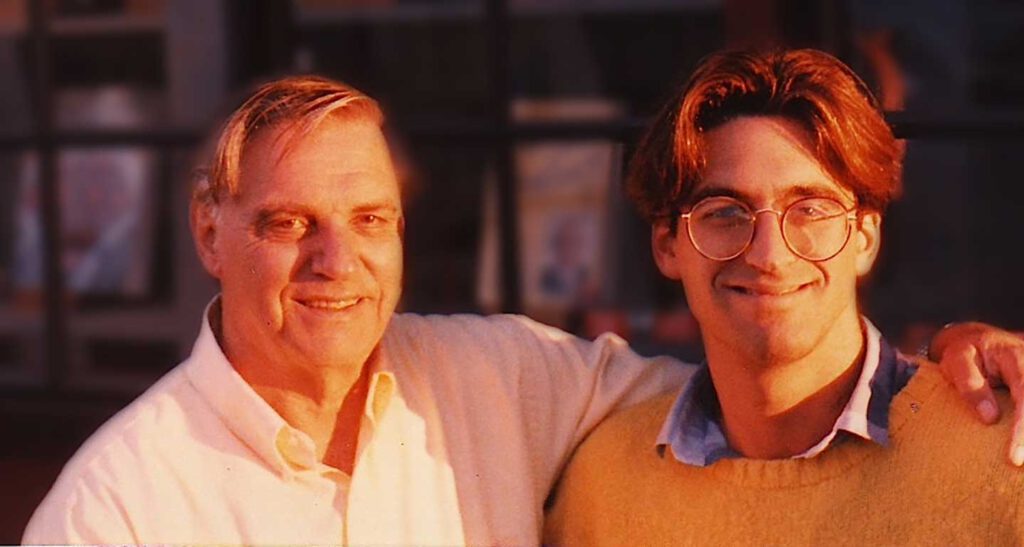

Many years later, Cathy and I produced/directed “The Story of Fathers and Sons” and at a prestigious Hollywood premiere, from the stage I publicly invited all the men involved in the film to come up on stage with me and made a special point to ask my father to join us. From the back of the theater he refused until i asked 3 times, but as he came forward the other men and boys encouraged him with great joy and fellowship and i vividly remember his facial expresssions of awkwardness and uneasiness give way to genuine pleasure and satisfaction.

During the making of that film, i had repeatedly called him and asked him all the questions that so many of us men never ask our fathers. He didn’t like it. “What’s wrong with you?” he’d say, “Are you in therapy or something?” he’d ask in a disapproving tone. Just as he didn’t think film making was a real job, so too were therapists not real job holders.

The biggest of my questions was very hard for me to even ask, a question that came up from a very wounded place in me. He resisted anwering too. It took repeated conversations to politely but actively compell him to answer.

You see, as a boy he had never played ball with me. I grew up years behind the other boys in hand eye coordiantion and suffered constantly on the football and baseball fields. In time, i became a hippie a learned to juggle and to my great surprise, found that i was fully capable of cathcing a ball – but the lack of father-son ball play had already deeply scarred me.

“Why did you never play ball with me? Why did we never play catch?”

Finally, at my insistance, he gave a true answer.

“I never played catch with you because my father never played catch with me. I don’t really know how to throw a ball. We were too poor. I couldn’t teach you how to throw a ball because … I don’t know how to throw a ball.”

and suddenly i remembered a time as a boy watching him play volleyball at the science lab with his co-workers. It was a painful memory. I was so totally incapable of playing he was humiliated every time the ball came his way, just as i had been when out in right field in my own boyhood. All that anger i had felt for years, burning with fury at something he had withheld … was sour and horrible and totally wrong. I didn’t know what to do with all that anger, i still felt it inside me, but now … it was tempered by understanding.

It wasn’t my humiliation.

It was our humiliation.

He never really outgrew that inner malnourished child. He was smart and articulate, but like many men of his generation not especially skilled at talking about his feelings. Plus, although i never doubted that he loved me and indeed he told me many times that he did; he didn’t learn what love was in his family growing up. His parents were too poor and desparate and struggling to be loving. Their home was filled with screaming fights over money, or the lack of it. He really was raised by his sister Helen, kind in her own way; but raising him out of duty and pity. He never really felt at ease with love. It wasn’t as good as a retirement plan. It wasn’t something that you could rely on. It wasn’t something that could put food on the table.

But for all that, let me say again, he loved me. and i loved him. There is no doubt, imperfect as he was, he did the best he could. When he passed away, i grieved. But we had had the hard conversations. There were no unanwered big questions. There was none of that pain. I can forgive him and accept him and love him for who he was. and honor his memory now as i type these words.

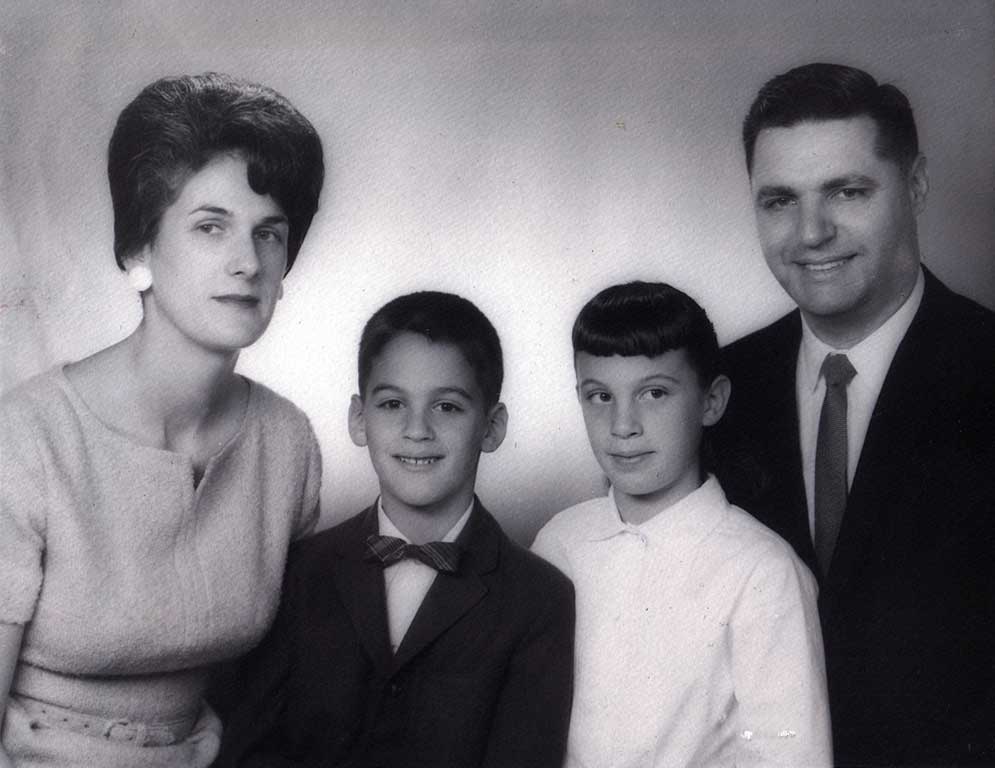

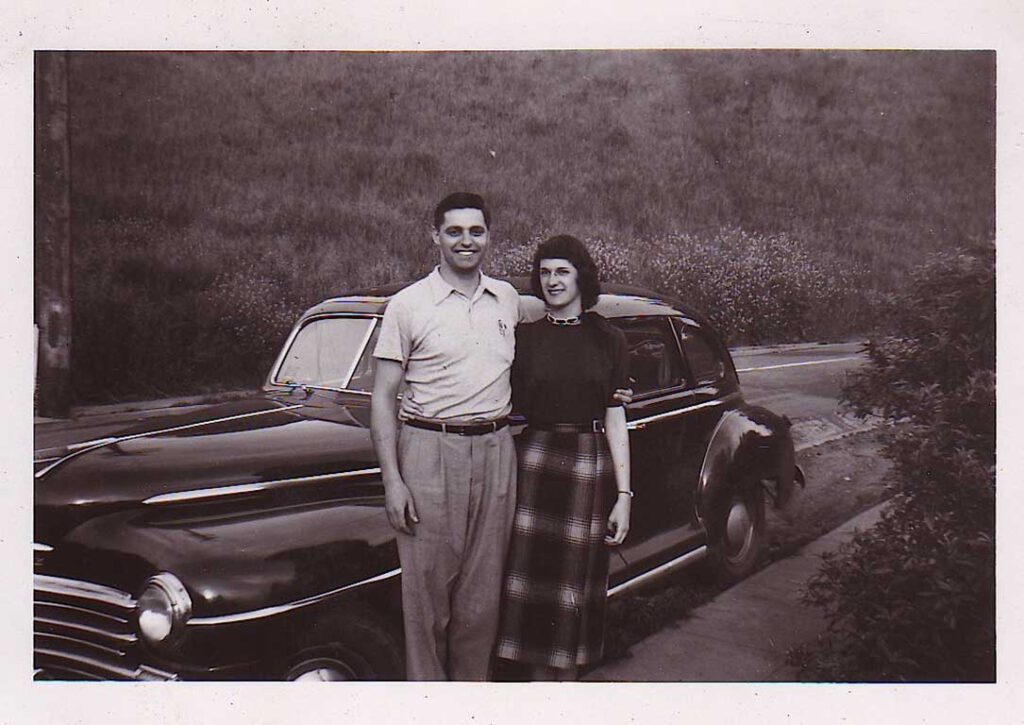

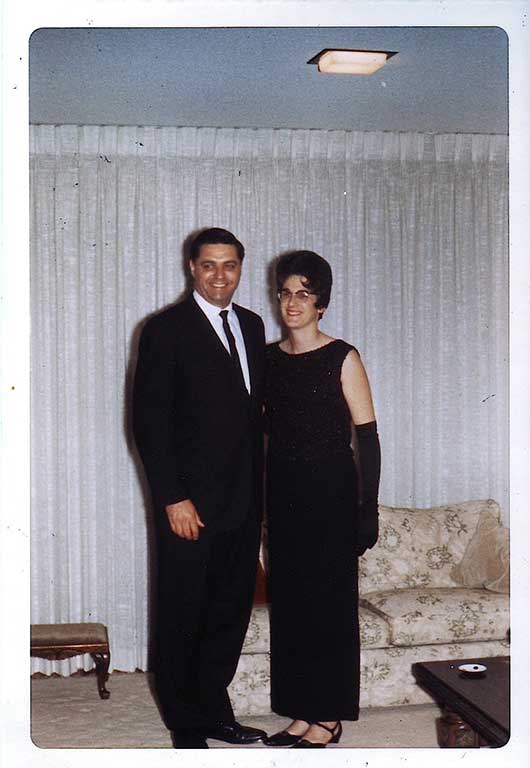

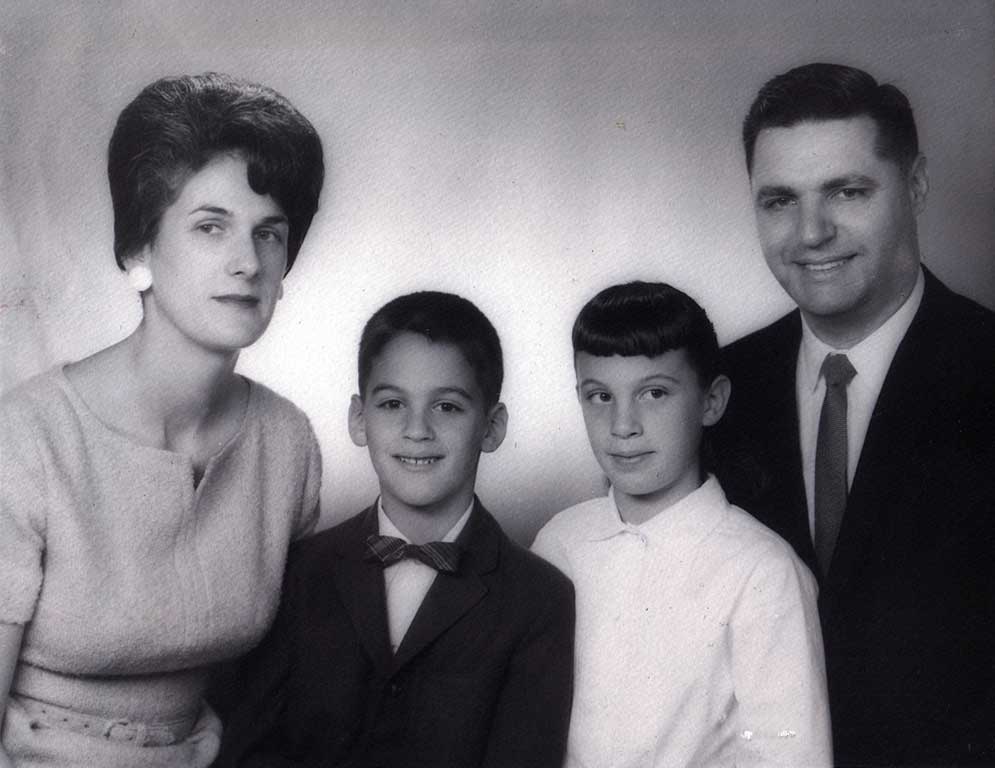

Ralph Weimberg

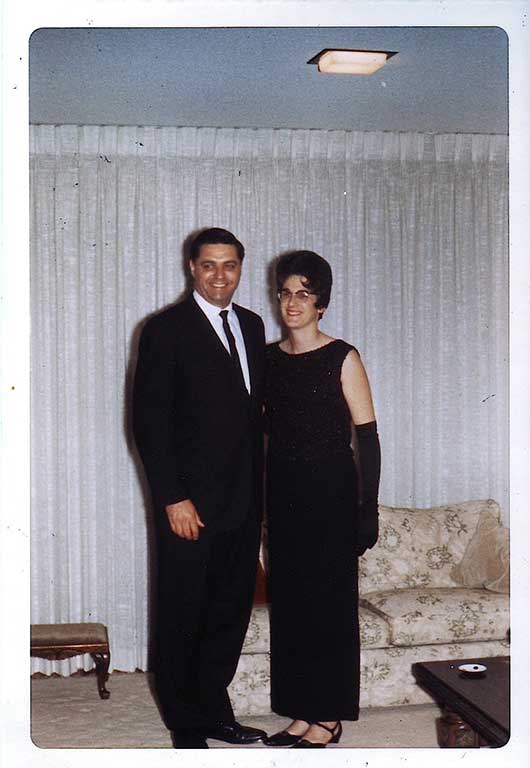

born: Dec 22, 1924

married: June 20,1952

died: March 15, 2003

age 78 years

Meanwhile ...

In 2017, I was diagnosed with colon cancer. I spent the next 5 years fighting and winning my battle for health.

But … I had to prioritize my health. I couldn’t work. I had to cut back, so i decided to close my office, move out of the space that i had joyously worked in for 17 years, and pack up 17 years worth of film making gear and posters and videos and photos and … everything. Alot of … personal items.

It was an emotional time.

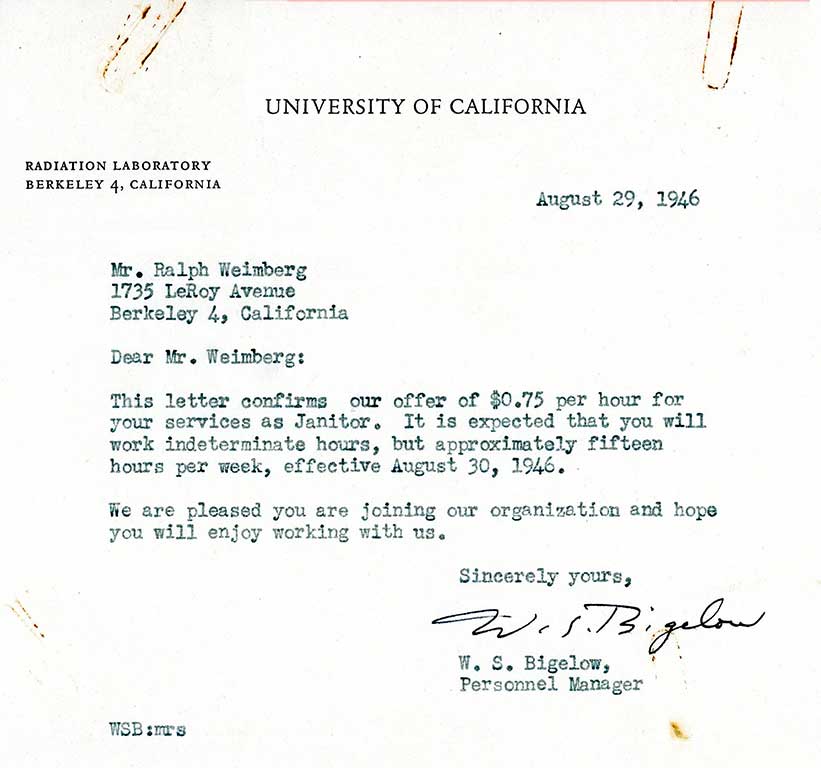

As I moved out of my office, I found the letter posted below:

a job offer to my dad, from 1946.

75¢ an hour.

Janitor, at the Radiation Lab of University of California, Berkeley (Cal).

He spent his entire college life at Cal, 8 years from undergraduate through to his completed PhD in Microbiology. This job likely the beginning of what would prove to be his lifetime’s work – science.

rest in peace dad. and thank you. and fwiw … i can throw a ball now just fine.

Related Articles

What is it like to be interviewed by Luna Productions?

if ya wanna know - and the prepare to enjoy yourself!